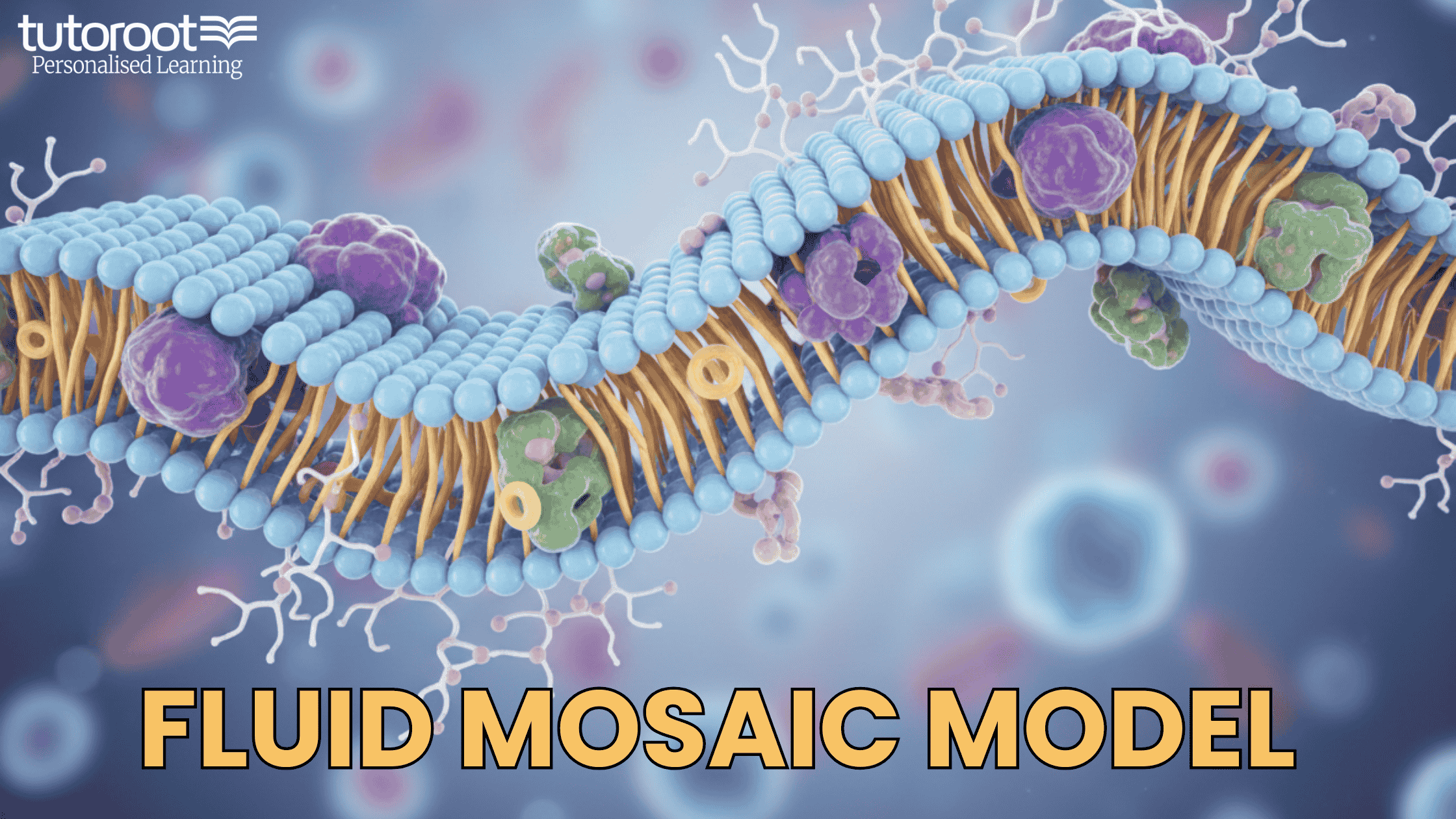

What is Fluid Mosaic Model Theory? Fluid Mosaic Model Diagram

When it comes to understanding how life exists at a microscopic level, the Fluid Mosaic Model is the gold standard. Proposed by S. Jonathan Singer and Garth L. Nicolson in 1972, this theory revolutionized biology by shifting our view of the cell membrane from a static “sandwich” to a vibrant, shifting sea of molecules.

Today, this model remains the foundation for students preparing for NEET, IB, and IGCSE biology. In this article, we’ll break down the structure, components, and factors that make the plasma membrane a masterpiece of cellular engineering.

What is the Fluid Mosaic Model Theory?

At its core, the Fluid Mosaic Model describes the plasma membrane as a “mosaic” of various components—including phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins—that move “fluidly” within the plane of the membrane.

Imagine a crowded swimming pool filled with colorful floats. The water (the lipid bilayer) allows the floats (proteins) to drift around, interacting and shifting positions constantly. This dynamic nature is essential for the cell to communicate, transport nutrients, and maintain its shape.

The Backbone: Phospholipid Bilayer

The primary fabric of the membrane is the phospholipid bilayer. Each phospholipid molecule is amphipathic, meaning it has two distinct personalities:

-

Hydrophilic Head: Attracted to water, these face the exterior and interior of the cell.

-

Hydrophobic Tail: Water-fearing fatty acid chains that hide away in the center, creating a protected oily core.

Pro-Tip for Students: This arrangement is spontaneous. Because cells live in watery environments, phospholipids naturally align into this “double-layer” to keep their tails dry!

Key Components of the Mosaic

1. Proteins: The “Floats” of the Membrane

Proteins make up about 50% of the membrane’s mass and handle the “work.”

-

Integral (Transmembrane) Proteins: These span across the entire bilayer. They act as “tunnels” (channels) for ions or “pumps” for active transport.

-

Peripheral Proteins: These sit on the surface. They are often involved in cell signaling or maintaining the cell’s internal skeleton (cytoskeleton).

2. Cholesterol: The Fluidity Buffer

Often misunderstood, cholesterol is vital. It acts like a temperature regulator:

-

In Cold Temperatures: It prevents phospholipids from packing too tightly (staying fluid).

-

In Warm Temperatures: It pulls them together to prevent the membrane from becoming too “leaky” or falling apart.

3. Carbohydrates: The Cell’s ID Tags

Found only on the outer surface, these are attached to proteins (glycoproteins) or lipids (glycolipids). They function as identification markers, helping your immune system distinguish between “self” and “foreign” cells.

Factors That Control Membrane Fluidity

The membrane isn’t just “liquid”—it’s a carefully balanced state of matter. Three main factors influence this:

-

Temperature: Heat increases kinetic energy, making the membrane more fluid. Cold makes it more rigid.

-

Fatty Acid Saturation: * Saturated tails are straight and pack tightly (less fluid).

-

Unsaturated tails have “kinks” (double bonds) that push neighbors away (more fluid).

-

-

Cholesterol Content: As mentioned, it keeps the fluidity in the “Goldilocks zone”—not too hard, not too soft.

Critical Functions of the Plasma Membrane

-

Selective Permeability: It decides what enters (like glucose) and what stays out (like toxins).

-

Cell Recognition: Essential for tissue formation and fighting off viruses.

-

Signal Transduction: Receptors on the membrane catch “messages” (hormones) and tell the cell how to react.

-

Cell Adhesion: Like cellular glue, it helps cells stick together to form organs.

Common Misconceptions (NEET & IB Prep)

-

“The membrane is a solid wall”: False. It is a liquid-crystal state. If it were solid, proteins couldn’t move to send signals.

-

“Molecules stop moving at equilibrium”: False. In a fluid model, molecules are always moving; at equilibrium, they just move back and forth at the same rate.

-

“Ions pass through the lipid tails”: False. Highly charged ions cannot cross the oily core and must use protein channels.

Master Biology Concepts with Tutoroot

Complex theories like the Fluid Mosaic Model are the building blocks of high-scoring biology exams. While blogs provide a great overview, a personalized touch can be the difference between a “good” grade and an “exceptional” one.

At Tutoroot, we specialize in simplifying high-difficulty topics for NEET, IB, and IGCSE students. Our expert biology tutors use interactive digital tools to bring the microscopic world to life.

Why Students Excel with Tutoroot:

-

Interactive 1-on-1 Sessions: Get your specific doubts cleared instantly.

-

NEET & IB Focused Strategy: We focus on the high-weightage topics that actually appear in exams.

-

Flexible Learning: Study from the comfort of home with schedules that fit your busy life.

Ready to see the Fluid Mosaic Model (and much more) in a new light? Stop struggling with complex diagrams alone. Join thousands of successful students who have transformed their grades.

FAQs

1. Who proposed the Fluid Mosaic Model? It was proposed by S.J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson in 1972.

2. What does “Mosaic” mean in this model? It refers to the pattern of different molecules (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids) scattered throughout the membrane, similar to a mosaic tile floor.

3. Does the cell membrane require ATP to stay fluid? No, fluidity is a physical property based on temperature and lipid composition. However, moving certain molecules across it (Active Transport) does require ATP.

4. Why is the Fluid Mosaic Model still relevant in 2026? While we have discovered more details like “Lipid Rafts,” the basic principles of fluidity and protein mosaicism remain the most accurate way to describe membrane behavior.